I came across this gem last week and knew it had to be shared. It's a 1945 documentary entitled, "How a Bicycle is Made." As described by the British Council Film website, the video depicts the design and manufacture of Raleigh bicycles in the UK.

It's a little over 17 minutes long, but it's worth every second. Take a look:

A few quick observations about the window into the past this film gives us. First of all, this is a labor intensive operation, and skilled labor at that (decidedly male too...). It takes a lot of elbow grease and know-how to successfully complete the many stages of producing a bicycle, from drawing the concepts, to welding, smelting, strengthening and purifying the metal, and assembling of all of the intricate parts into a complete model. Sidenote: Extra points if you can find the mechanic smelting in a sweater vest. I am sure modern day bicycle manufacture needs a lot fewer employees and uses a more mechanized approach. Secondly, I think operations like these birthed agencies like OSHA. I can't imagine the health risks these workers assumed by inhaling fumes and dealing with open baths of chemicals strong enough to rust-proof steel. But thankfully these are hazards of a bygone era.

As dated as the video may seem, some of it is startlingly relevant to the discussion today concerning the role bicycles play in our everyday lives. As the narrator concludes (starting at the 16:47 mark), "A bicycle is a comfortable and cheap way of getting about. A great boon

to man [and woman]. Ideal for shopping, easy to park, handy for work. A faithful

friend, ever ready to take tired workers back home, and after work to

bring relaxation, health, and happiness."

Monday, May 21, 2012

Sunday, May 13, 2012

Rising Gas Prices, Part Two: What Aren't We Paying For?

This post is the second in a series on the soaring price of gasoline. I originally thought I could fit all of these ideas in one post -- boy was I wrong. If you missed out on Part One, read it here.

One of my favorite finds in the enviro-journalism world recently has been Climate Desk, a collaborative reporting effort from some of my already favorite news outlets like Grist, Mother Jones, and The Atlantic. They consistently cover the issues that I have on my radar, and do it very well. My investigation into the rising price of gasoline is no exception. I encourage you to click through their slideshow which covers the ins and outs of the issue, but I will share with you two of the highlights from it here.

The first is a video of Christopher Knittel, professor of energy economics at MIT, who speaks about the "true social cost of a gallon of gasoline."

He hits a lot of important points in a short clip, including how gas is linked on the global market to the price of oil, four types of externalities (a larger military, pollution and human health effects, climate change, and an economy susceptible to oil price shocks), how the price of gasoline affects our decision-making processes as consumers, and the fact that much of our modern way of life is predicated on cheap gasoline.

One of his most perspective-shifting comments is surely, "Even though the price of gas is historically high these days it turns out there's a lot of costs that society bears of our decisions to buy gasoline that aren't incorporated in the price." Maybe we've gotten away with a cheaper price than we really could have been paying all this time.

The second clip takes Knittel's ideas one step further, exploring the question: What contributes to the cost of a gallon of gasoline? In the process it explains what maybe should be included, but isn't. Take a look at this animation from Climate Desk partner, the Center for Investigative Reporting:

Nothing is more telling than this quote, "What's the true price of gas? It's a lot more than what we pay at the pump." I appreciate the way they quantify the total cost of externalities (somewhere between $550 billion and $1.7 trillion) and also the pollution impact of a gallon of gasoline, much of which accumulates before it even reaches the tank of your car.

These videos effectively capture the social and environmental costs not reflected in the price we pay, borne by others or even by us at a later date. Deferring risk and responsibility to separate communities or future generations in the name of near-term gain -- now where have I heard that before?

One of my favorite finds in the enviro-journalism world recently has been Climate Desk, a collaborative reporting effort from some of my already favorite news outlets like Grist, Mother Jones, and The Atlantic. They consistently cover the issues that I have on my radar, and do it very well. My investigation into the rising price of gasoline is no exception. I encourage you to click through their slideshow which covers the ins and outs of the issue, but I will share with you two of the highlights from it here.

The first is a video of Christopher Knittel, professor of energy economics at MIT, who speaks about the "true social cost of a gallon of gasoline."

He hits a lot of important points in a short clip, including how gas is linked on the global market to the price of oil, four types of externalities (a larger military, pollution and human health effects, climate change, and an economy susceptible to oil price shocks), how the price of gasoline affects our decision-making processes as consumers, and the fact that much of our modern way of life is predicated on cheap gasoline.

One of his most perspective-shifting comments is surely, "Even though the price of gas is historically high these days it turns out there's a lot of costs that society bears of our decisions to buy gasoline that aren't incorporated in the price." Maybe we've gotten away with a cheaper price than we really could have been paying all this time.

The second clip takes Knittel's ideas one step further, exploring the question: What contributes to the cost of a gallon of gasoline? In the process it explains what maybe should be included, but isn't. Take a look at this animation from Climate Desk partner, the Center for Investigative Reporting:

Nothing is more telling than this quote, "What's the true price of gas? It's a lot more than what we pay at the pump." I appreciate the way they quantify the total cost of externalities (somewhere between $550 billion and $1.7 trillion) and also the pollution impact of a gallon of gasoline, much of which accumulates before it even reaches the tank of your car.

These videos effectively capture the social and environmental costs not reflected in the price we pay, borne by others or even by us at a later date. Deferring risk and responsibility to separate communities or future generations in the name of near-term gain -- now where have I heard that before?

Wednesday, April 25, 2012

Rising Gas Prices, Part One: Pain at the Pump, World Markets

Nothing speaks louder to our addiction to oil than the panic over rising gas prices. I've felt it too, I am driving a lot, and I mean A LOT to and from work these days. Just check out the tab I ran up at the pump during a recent fill-up. For the past two months, gas in Connecticut has steadily risen to just under $4.00/gallon when the above pic was taken. The upward trend hasn't slowed though, and more and more stations have surpassed the $4.00 mark for regular unleaded. Even when I shop for the very best price among the nearly two-dozen filling stations I pass during my commute (it's true, regional variation doesn't change that much), I can't best the $4.00 beast. Soon I'll be living and working in a place where I won't need to own a car, but that day hasn't come just yet (and it won't stop GM from enlisting MTV to help draw us young whippersnappers into the showroom).

If you follow me on twitter (@agmaynard) you'll remember I began on this train of thought a few weeks ago in a series of tweets about the origins of the pain at the pump panic. My thinking out loud went like this:

The response "use less oil" to those worried about rising gas prices must sting to the subset whose livelihoods depend on driving to work//But keeping costs cheap perpetuates dependency on that system, hmm... (assuming we can have any control over oil markets in the 1st place)//Hint: no single agent does, really, especially not @BarackObama//Doesn't the question then become, how do we gradually increase cost to shift paradigm while assisting the most impacted?//Increasing costs = decreasing oil subsidies, transfer the difference to fund renewable tech? But then there's the problem of design...//...that facilitates long car commutes in the first place and is a longer-term fix. Need to do some more thinking on this.//This comes to mind for some reason: "The only way not to think about money is to have a great deal of it" - Edith Wharton, House of Mirth//Panic comes partly from the pain at the pump, but I'm guessing more so from the anxious feeling that they have no other choice but to pay.//That panic goes away if there are viable (and cheaper) alternatives.The parts I want to focus on are the beginning and the end, where I attempt to identify the motive of those beating the cheap gas war drums. For the purposes of this post let's ignore the middle bit about transferring oil subsidies to renewables R&D. What I meant to say there was more along the lines of assistance programs for those most impacted by rising gas prices, but regardless I don't think that'd be an even 1:1 exchange. Then of course there are the obvious political ramifications and deadlocks necessary to thwart Obama's socialist agenda ;)

SO, pain at the pump. What is it? Fear. Anxiety. A sense of being trapped, locked into a system, at the mercy of fluctuating global markets. Is anything more maddening, or hopeless, for a household struggling to pay the bills, who simply can't afford a bigger bite out of their income? Especially in this economy. This is a very real fear for those living from month to month, paycheck to paycheck. Budget dependability? What a pipeline, er-- I mean pipedream.

This panic reminds me of a similar fervor displayed by some residents from my hometown over a proposed Costco development two years ago. The retail giant would provide jobs and economic development, they said, and thus the proposed megastore should be unanimously approved by the Planning and Zoning Commission. During interviews with local planning officials for a paper I wrote on the plan, they told me that for these residents Costco symbolized relief from the sometimes crippling financial stress associated with the recession. It didn't matter if the developer's jobs and salary claims were overstated or that much of Costco's labor force doesn't originate in its host communities. It represented stability, and an escape from the doldrums of a down economy.

What's important to realize though is that I grew up in small-town Connecticut. We have a Walmart that was only approved because it was an as-of-right development (aka it conformed to all existing zoning regulations). What this means though, is that we are home to one of the smallest -- if not THE smallest -- Walmarts in the country at just over 85,000 square feet. A request at the time to expand the building into the surrounding parking lot was denied. The proposed Costco would have been almost double the size at 150,000 SF. In my opinion (when do well-researched opinions become facts, anyway?) it would have been disastrous for the intimate character of the town that, ironically, makes Guilford such a vibrant economic landscape in the first place. I digress; this is a post about gas prices, after all. The takeaway from this anecdote, though, is that sometimes people jump at short-term fixes to chronic problems because they don't have the luxury of looking further into the future. Their immediate needs aren't being met, or there's a very real threat that in the near term they won't be met.

CNN's John King summarized this message well during a broadcast a few weeks ago: "Your views on energy are driven by your bottom line."

So the next logical question is what can we do about alleviating pain at the pump, or avoiding it entirely? Drill baby drill, right? Riiiiiiiiiiight? I say no, and here's why. I'll be the first one to admit that I am not an authority on global oil markets, but I've been sifting through the literature for the last month or two and if I've learned one thing it's this: We're all connected. Take this graph, for example.

The United States is connected to other global economies through the intricate web of petroleum production and distribution networks. It is incredibly difficult for one nation, even the US which admittedly uses a disproportionate amount of global supply, to tip the scales through increased domestic production. When prices go up for us, they go up for (most) everybody else. The same goes for when prices drop, but there may not be much reason to hope for cheaper gas in the future.

Here's the reality as we move further into the 21st Century: Gas prices are not going to go down. At least not over the long-term. As developing countries like China and India continue to industrialize and as their bulging populations rise into the middle class, they are going to demand a higher standard of living (implication here, powered by fossil fuels). They have quite the role models (U-S-A, U-S-A!) and Econ 101 says that when demand for a product increases, so does price.

So if we're locked into the global market and prices will steadily go up and up and up regardless of an increase in domestic production, what are our other options? How do we get some relief from that pain at the pump?

In my next post I'll explore some of the alternatives to emptying your wallet at the gas station. I'll focus mainly on efficiency, hybrid/electric vehicles, and algae-based biofuels. Stay tuned for Part Two of this Rising Gas Prices series.

Sunday, March 11, 2012

Paris, 1928

Last year in a post entitled Barcelona, 1908 I shared an video shot from the front of a streetcar navigating the avenues of the title city a little over a century ago. As you'll remember (if you don't, feel free to go back and take a look), I commented on the complexity of the methods of mobility that took up street-space in relative harmony. From pedestrians, to bicyclists, to carriages, to even a few early automobiles, the streets were a genuine mix of modes of transportation. Now I bring you back to an early 20th Century European city, but this time it's Paris, 1928.

The differences are immediately apparent. There are many more automobiles, and pedestrians largely keep to the sidewalks instead of weaving in front of the streetcar-mounted camera as they did in Barcelona. It's interesting to see the changes and the prevalence of the automobile only twenty years after the first clip.

In 1928 Paris you will notice a city struggling with the pressures of this increase in automobile traffic. Street activity, largely unregulated and unsupervised before, now necessitates direction from officers who stand down oncoming vehicles. At the 1:18 mark, the camera captures the somewhat organized chaos of the bustling intersection where one car drifts into the flow of oncoming traffic. But no one really has right of way anyway and there aren't even lanes, so who is at fault here? Here's a frightening thought -- think of being on the road with that many new drivers, operating largely unfamiliar technology in a space with little oversight. No wonder the pedestrians stick to the sidewalks except to cross...

My takeaway from this video (in reference to the first) is the pace at which automobiles infiltrated the centers of these old cities that for centuries had operated largely on foot traffic as the primary mode of transportation. More autos traveling at higher speeds on cramped streets relegated pedestrians to the sidewalk where they understandably felt more safe. This separation transformed the function of these streets, and had serious implications for them as public spaces. This compartmentalization of uses is the challenge the shared space movement, and to a certain extent the complete streets initiative, attempt to correct through redesign and reprogramming of streets, thereby changing public perception of streets as car-only zones to ones accepting and emboldening of more diverse modes of transportation.

Sometimes we must look back in order to move forward.

The differences are immediately apparent. There are many more automobiles, and pedestrians largely keep to the sidewalks instead of weaving in front of the streetcar-mounted camera as they did in Barcelona. It's interesting to see the changes and the prevalence of the automobile only twenty years after the first clip.

In 1928 Paris you will notice a city struggling with the pressures of this increase in automobile traffic. Street activity, largely unregulated and unsupervised before, now necessitates direction from officers who stand down oncoming vehicles. At the 1:18 mark, the camera captures the somewhat organized chaos of the bustling intersection where one car drifts into the flow of oncoming traffic. But no one really has right of way anyway and there aren't even lanes, so who is at fault here? Here's a frightening thought -- think of being on the road with that many new drivers, operating largely unfamiliar technology in a space with little oversight. No wonder the pedestrians stick to the sidewalks except to cross...

My takeaway from this video (in reference to the first) is the pace at which automobiles infiltrated the centers of these old cities that for centuries had operated largely on foot traffic as the primary mode of transportation. More autos traveling at higher speeds on cramped streets relegated pedestrians to the sidewalk where they understandably felt more safe. This separation transformed the function of these streets, and had serious implications for them as public spaces. This compartmentalization of uses is the challenge the shared space movement, and to a certain extent the complete streets initiative, attempt to correct through redesign and reprogramming of streets, thereby changing public perception of streets as car-only zones to ones accepting and emboldening of more diverse modes of transportation.

Sometimes we must look back in order to move forward.

Sunday, February 26, 2012

Back in Action//Analyst versus Advocate

*wipes away cobwebs across computer screen*

Hey all, it's me. Yeah me. Remember way back when I actually contributed to this blog? I know I've been absent for quite some time--it's interesting how unplanned breaks can balloon into extended sabbaticals--but here I am, back in action.

So what have I been up to these past six months, you ask? Well in October I started working at the Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection. I have contributed to numerous projects so far, including writing press releases and other copy for the Communications Office, administering an energy efficiency program charged with reducing energy consumption in state-owned buildings by 10 percent in the next year, and I'm also the mind behind a massive restructuring effort for the energy-related content on the agency's website.

Overall, working at DEEP has been an incredible experience. Having a boss and supervisors who trust in my abilities and challenge me to meet their high expectations is rewarding. It's also been a unique opportunity to see the inner workings of government itself, often given a bad rap for being a bloated mess of bureaucracy and red tape. My impression of DEEP couldn't be further from that perception. Thanks to a commitment to environmental goals from Connecticut Governor Dannel Malloy and the leadership of DEEP Commissioner Daniel Esty, the Department is well-poised to drive real change in a state in desperate need of better economic performance. And that's the thing, environmental policy and programs are viewed as our ticket out of the recession. The conversation is about how we achieve environmental and energy goals while stimulating local job growth. My time at DEEP has shown me how there is a growing opportunity for E&E policy action at the state level, especially given the failure of Congress to pass any meaningful and comprehensive climate legislation.

Now that I've updated you on one of the major goings-on in my life since I left you, let's get down to business. For my first post post-hiatus (see what I did there), let's discuss Analysts versus Advocates.

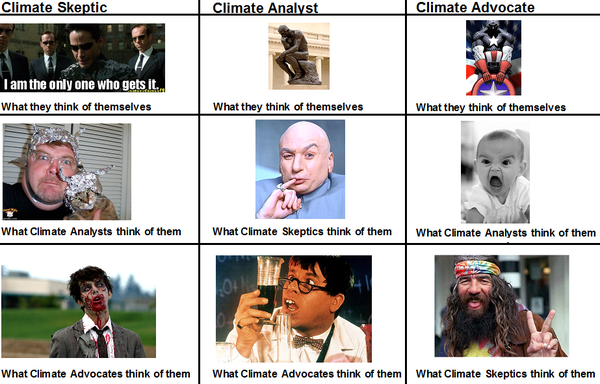

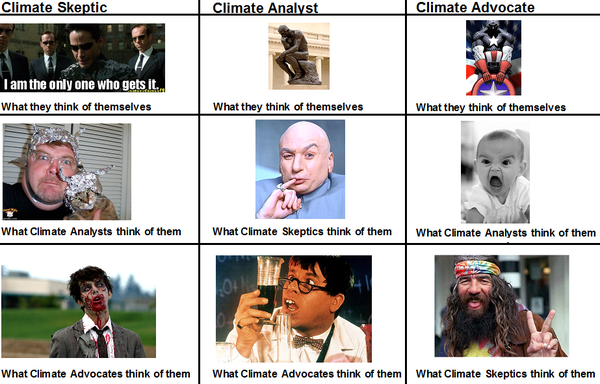

University of British Columbia professor George Hoberg recently posted this explanation of climate-political mindsets to his blog, GreenPolicyProf. Hoberg describes how there are three approaches to climate politics--skeptic, analyst, and advocate. He devotes most of the post to the last two, and describes skepticism as "too mysterious" to warrant extended investigation. As someone who has assumed both the analyst and advocate roles in the last year even, I found the piece an interesting critique of each.

Here are the fundamental differences between analysts and advocates, as explained by Hoberg:

Hoberg again:

When I set out to write this post I was worried I would be out of blogging shape. I really have missed writing on a regular basis on a topic I care deeply about. I can't promise anything, but I do plan to post more and I have a few ideas in the works so we'll see where we end up.

Happy reading, reflecting, world-changing.

Hey all, it's me. Yeah me. Remember way back when I actually contributed to this blog? I know I've been absent for quite some time--it's interesting how unplanned breaks can balloon into extended sabbaticals--but here I am, back in action.

So what have I been up to these past six months, you ask? Well in October I started working at the Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection. I have contributed to numerous projects so far, including writing press releases and other copy for the Communications Office, administering an energy efficiency program charged with reducing energy consumption in state-owned buildings by 10 percent in the next year, and I'm also the mind behind a massive restructuring effort for the energy-related content on the agency's website.

Overall, working at DEEP has been an incredible experience. Having a boss and supervisors who trust in my abilities and challenge me to meet their high expectations is rewarding. It's also been a unique opportunity to see the inner workings of government itself, often given a bad rap for being a bloated mess of bureaucracy and red tape. My impression of DEEP couldn't be further from that perception. Thanks to a commitment to environmental goals from Connecticut Governor Dannel Malloy and the leadership of DEEP Commissioner Daniel Esty, the Department is well-poised to drive real change in a state in desperate need of better economic performance. And that's the thing, environmental policy and programs are viewed as our ticket out of the recession. The conversation is about how we achieve environmental and energy goals while stimulating local job growth. My time at DEEP has shown me how there is a growing opportunity for E&E policy action at the state level, especially given the failure of Congress to pass any meaningful and comprehensive climate legislation.

Now that I've updated you on one of the major goings-on in my life since I left you, let's get down to business. For my first post post-hiatus (see what I did there), let's discuss Analysts versus Advocates.

University of British Columbia professor George Hoberg recently posted this explanation of climate-political mindsets to his blog, GreenPolicyProf. Hoberg describes how there are three approaches to climate politics--skeptic, analyst, and advocate. He devotes most of the post to the last two, and describes skepticism as "too mysterious" to warrant extended investigation. As someone who has assumed both the analyst and advocate roles in the last year even, I found the piece an interesting critique of each.

Here are the fundamental differences between analysts and advocates, as explained by Hoberg:

The logics of analysis and advocacy are fundamentally different. The analyst is guided by aspirations for truth and well-reasoned argument, and guided largely by the value of maximizing the cost-effectiveness of solutions. They chaff against exaggerations and misuse of data by advocates on all sides, and search for the best reasoned argument for the most efficient path forward.Using the Keystone XL Pipeline debate as an example, he says the typical analyst mind evaluates the proposal as follows. We need oil--> building it won't significantly contribute to climate change--> Canada is a friendly trade partner --> approve the pipeline. Advocates on the other hand view the pipeline as a symbol for the larger environmental crises, and use it as political capital to push their overall message.

In contrast, the climate advocate is trying to maximize political leverage in an effort to foster systemic transformation of the energy system. The logic of political action and movement building is different from the logic of policy efficiency. The advocate works to strategically frame problems and solutions that work politically, not those that best adhere to the standards of analytical rigor. Frequently, this involves exaggerated claims that aggravate the analyst.

Hoberg again:

[Bill] McKibben and his allies didn’t choose to draw a line in the sand on Keystone XL because it was the most cost-effective policy to reduce GHG emissions. They picked it because it made political sense given the state of the climate movement in US and global politics. Having failed so spectacularly at Copenhagen and then in the US Congress to get meaningful action, McKibben and Co. recognized that to have meaningful success, more direct action would be required to galvanize the intensity of preferences at the grassroots level needed to foster a powerful social movement. Keystone XL turned out to be a perfect short-term vehicle for that. It was a point of leverage they could use to focus concentrated pressure, and it turned out to be a spectacular success on its own terms.As someone still defining his professional and personal identity, I'd like to think I combine the advocate's passion for positive environmental change with the analyst's pragmatism. I don't think the two are necessarily exclusive. In my mind the philosophical construct is more a sliding scale than distinct silos. I'll continue to think about how I define my approach to solving the environmental challenges we face in the 21st Century, and I encourage you to do the same.

When I set out to write this post I was worried I would be out of blogging shape. I really have missed writing on a regular basis on a topic I care deeply about. I can't promise anything, but I do plan to post more and I have a few ideas in the works so we'll see where we end up.

Happy reading, reflecting, world-changing.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)